Alătură-te comunității noastre!

Vezi cele mai recente știri & informații din piața de capital

The European Union and the G7 are preparing the 11th round of new sanctions to further isolate Russia, since Russian President Vladimir Putin decided to invade Ukraine in February 2022.

The more months go by, the easier the decision will be. The sanctions will continue to hurt the Russian economy, while their impact on Europe has become marginal. A good return on a small investment.

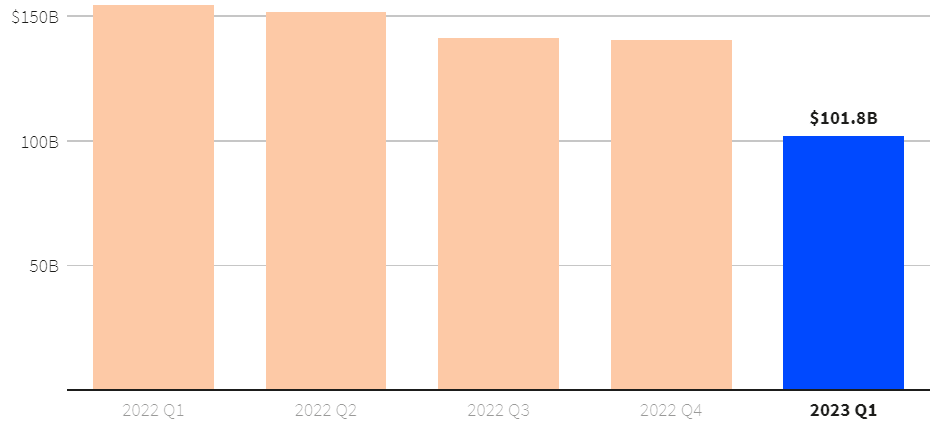

The sanctions have hit the Russian economy hard. According to the Russian Central Bank, the country’s merchandise exports fell to $102 billion in the first quarter of the year, down 28% from the previous quarter.

According to the Central Bank’s latest survey of economists, GDP will stagnate this year and shrink by more than 2% in 2022.

And the government is struggling to finance social benefits and the war effort.

Total value of Russian exports, in USD. Source: Central Bank of the Russian Federation | P. Briancon | Breakingviews | May 19, 2023

Other sanctions could include new restrictions on energy imports. After halting imports of Russian pipeline gas, Europe could ban imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Some EU governments want to lower the $60-per-barrel price cap on Russian crude oil from the Urals. This cap already allows China and India, the new major buyers of Russian oil, to demand rock-bottom prices from Moscow. A lower level would push those prices down further.

The G7 and the EU are also trying to crack down on sanctions violations. Over time, Russia and its allies have become experts at exploiting loopholes and leaks.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, for example, has noted the strange boom in exports from the UK, EU and US to Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, countries suspected of serving as hubs for re-exporting sanctioned products to Russia.

As Iran has shown-and Russia, too, after it was first sanctioned in 2014 for its annexation of Crimea-countries are finding ways to adapt to the new situation over time: Russia, for example, now meets its own food needs.

Further tightening is necessary to maintain pressure on Putin and damage the Russian economy. This may raise political questions. The question today is whether it would be wiser to extend sanctions to countries that help Russia evade them.

The most sensitive case is China. The U.S. wants to put some of its companies on the sanctions list, but Europe is resisting.

From an economic perspective, however, tougher sanctions are a clear case for the EU. Russia’s share of EU exports fell from 4% to 2% last year, and it continues to fall.

And with the exception of liquefied natural gas, energy imports of oil and gas have all but stopped. Economically, Russia no longer plays a role for Europe. Tightening the screw would be based on a sound cost-benefit analysis.

Vezi cele mai recente știri & informații din piața de capital